Seeing a brand-new ship start to rust is a shipowner’s nightmare. This corrosion weakens the steel hull, threatening structural integrity and leading to expensive, time-consuming repairs in dry-dock.

Metal anodes are fitted externally to a ship’s hull to provide cathodic protection. These anodes, made of a more reactive metal, corrode sacrificially in the seawater, protecting the less reactive steel hull from rusting.

Coming from Baoji—China’s titanium valley, I’ve spent years in the metal electrode business, supporting clients from industrial plating to marine engineering. A frequent question I get is why those metal blocks are bolted to a ship’s hull. The answer is cathodic protection. By attaching a more "active" metal, you create a galvanic cell where the anode corrodes instead of the ship. The goal is always the same: ensuring corrosion is controlled, predictable, and never a threat to safety.

How do sacrificial anodes protect ships in seawater?

It seems counterintuitive to fight corrosion by attaching a metal that corrodes even faster. This simple method, however, is a clever application of fundamental electrochemistry, turning corrosion into an ally.

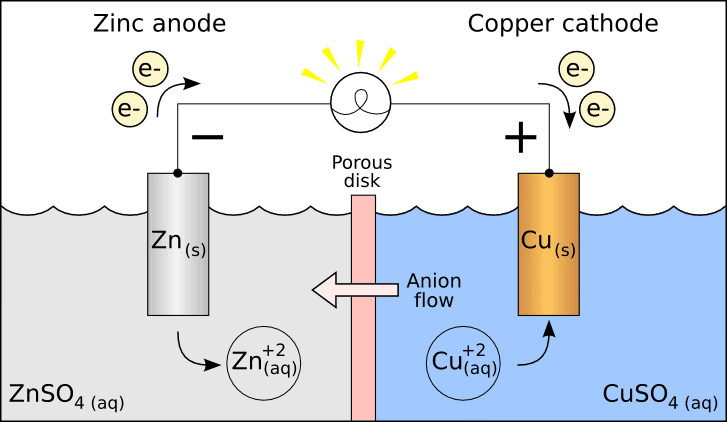

Sacrificial anodes protect a ship by creating a galvanic cell where they act as the anode. The anode corrodes and releases electrons, which flow to the steel hull (the cathode), preventing it from rusting.

In the highly conductive electrolyte of seawater, when two different metals like zinc and steel are connected, the more chemically active metal (zinc) starts to dissolve. This process is oxidation, and it releases a flow of protective electrons. The steel hull accepts these electrons, which effectively stops the iron from oxidizing and forming rust. The sacrificial anode is "sacrificed" to protect the more valuable structure. It’s a simple, reliable, and powerless method of corrosion control. Think of the anode as a bodyguard that takes the hit to protect the VIP—the ship’s hull. This is the most basic form of cathodic protection and is essential for any steel structure submerged in the ocean.

The Electrochemical Team

- The Ship’s Hull (Steel): Becomes the cathode; it is protected and does not rust.

- The Seawater: Acts as the electrolyte, allowing electrons to flow.

- The Sacrificial Anode: Becomes the anode; it corrodes (is sacrificed) to protect the hull.

What metals are commonly used as ship hull anodes?

Choosing the wrong anode material can lead to failed protection or even accelerated corrosion. Different marine environments and hull materials require specific types of anodes to ensure the system works as intended.

The most common metals for sacrificial anodes on ships are zinc and aluminum alloys. Magnesium is also used, but it is typically too reactive for saltwater and is reserved for other applications.

The choice of metal is critical. The anode material must have a more negative electrochemical potential than steel to work correctly. Zinc has been the traditional choice for decades, especially for general saltwater service. Aluminum alloys are a more modern alternative, offering a lighter weight and higher capacity, making them very popular. I often explain to my clients that the specific alloy is more important than the base metal. For example, high-purity aluminum will form a passive layer and stop working, so it must be alloyed with indium or zinc to stay active. The same is true for zinc anodes.

Common Anode Materials at a Glance

| Anode Material | Primary Environment | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zinc Alloy | Saltwater | Reliable, predictable performance | Heavier, less capacity than aluminum |

| Aluminum Alloy | Saltwater, Brackish Water | Lightweight, higher electrical capacity | Can become passive if quality is poor |

| Magnesium | Freshwater | Very high driving voltage | Corrodes too quickly in saltwater |

How often do ship anodes need to be replaced?

You’ve installed anodes, but how long will they last? Forgetting to replace them on time can leave your vessel unprotected, leading to the very corrosion damage you sought to prevent.

Ship anodes typically need to be replaced every 3-5 years, but this schedule depends entirely on factors like anode size, water conditions, and the ship’s operating profile. Replacement is almost always done during scheduled dry-docking.

There is no single answer for anode lifespan. The replacement frequency is a calculated part of a ship’s maintenance plan. A vessel that spends a lot of time in warm, highly saline water will consume its anodes faster than a ship in colder, less saline water. Likewise, the quality and condition of the hull’s paint coating play a huge role; a poorly coated hull will demand more current from the anodes, causing them to deplete faster. Engineers calculate the required weight of the anode material to ensure it provides sufficient protection until the next planned dry-docking. Regular inspection is key to ensuring the protection system remains effective throughout the ship’s operational cycle.

Can titanium anodes be applied in marine corrosion protection?

You’re looking for a long-term, low-maintenance solution for corrosion. Sacrificial anodes work, but their need for regular replacement adds to operational costs and complexity over the vessel’s life.

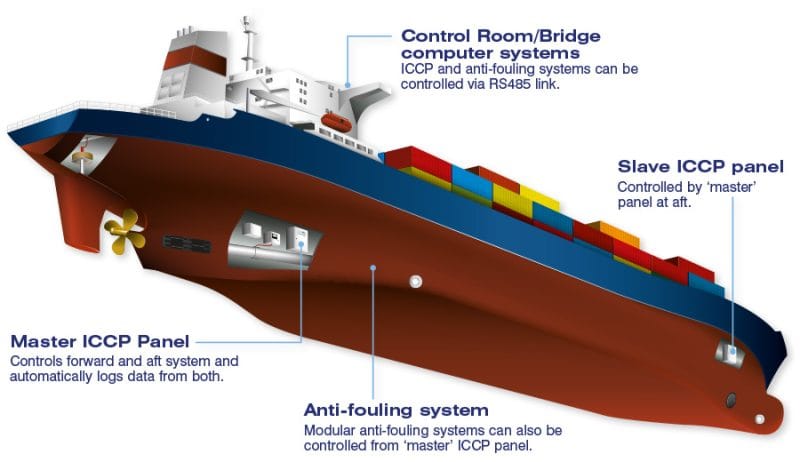

Yes, but not as a sacrificial anode. Titanium’s excellent corrosion resistance makes it an ideal material for long-life anodes in Impressed Current Cathodic Protection (ICCP) systems, where it does not get consumed.

Titanium is actually less reactive than steel, so it cannot act as a sacrificial anode to protect it. Instead, its incredible resistance to seawater corrosion makes it the perfect foundation for a different kind of protection system. In an ICCP system, a titanium anode coated with a Mixed Metal Oxide (MMO) is connected to a power supply. The power supply provides the protective current, and the titanium anode simply serves as a durable, non-consumable distributor for that current. This is a high-tech solution that offers precise, long-lasting protection without the need to replace anodes. Due to its durability and long service life, titanium is already used for critical marine components like propeller shafts, piping systems, and offshore structures. Its high initial cost is often offset by significantly lower maintenance needs over the life of the vessel.

Conclusion

External anodes protect a ship’s hull through cathodic protection. While traditional sacrificial anodes of zinc or aluminum are common, advanced systems use non-consumable MMO-coated titanium anodes for long-term, stable protection.

2 Responses

oobviously like your web-site however yyou need to check

the spellinng on quite a few of your posts.

Many of them are rife with spelling problems and I find iit very

bothersome to tell the truth on the other hand I wipl certainly come again again. https://meds24.sbs/

well noted, I will pay more attention on it to improve.